The data reveals how Texas has become the operational center of the Trump administration’s nationwide deportation strategy, leveraging state-federal cooperation to expand detentions — even of immigrants without criminal histories.…

Border News

Different groups have been the center’s focus, but without a doubt, the crisis of disappearances that began with migrants and grew like the heads of a Hydra has been the most significant.

History

In November 1999, José Raúl Vera López was named bishop of the Diocese of Saltillo, taking canonical possession in March 2000. As the former coadjutor bishop to Samuel Ruiz in San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas, he established a diocesan center for human rights, offering socially displaced people advice and a platform to present their complaints and demands.

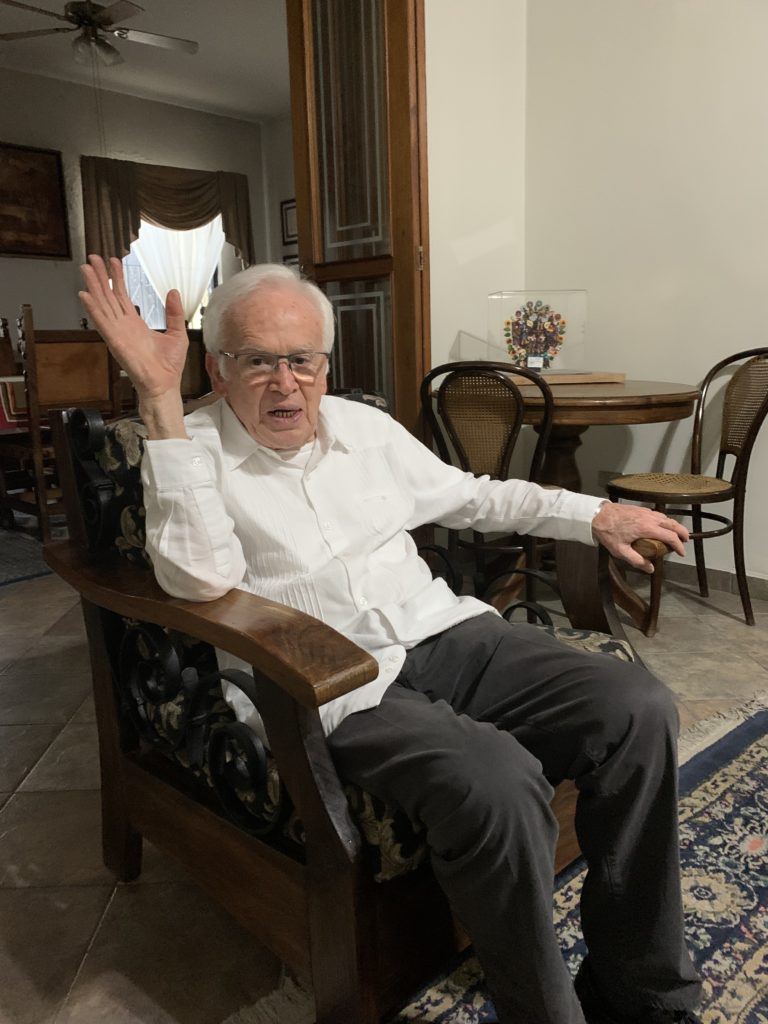

José Raúl Vera López, Bishop of the Diocese of Saltillo. Photo by Esmeralda Sanchez.

The area then covered what is now the Diocese of Piedras Negras, where two particularly vulnerable groups in Coahuila were migrants and miners, both suffering from deplorable living conditions. “I founded the Human Rights Center for migrants,” Vera recalls.

Miners “began to tell me how they had to work in very abusive conditions,” and migrants “were victims even of the police here.” Several collaborators joined the effort, including two nuns, a longtime ally, and communicator Jacqueline Campbell. On Sept. 22, 2004, the center became an association run by the Villarreal sisters from General Cepeda. The initial focus was on making human rights violations visible.

In 2006, the explosion at Mine 8 of Pasta de Conchos drew global attention to the Coal Region, exposing the disregard for miners’ lives by companies like Grupo México and their union representatives. Cristina Auerbach documented these events.

The social causes accumulated. The LGBTQ+ community is organized through its pastoral ministry and the emerging San Aelredo group. “The center became a civil platform for Don Raúl, allowing him to discuss these great tragedies and violence in the human rights framework, differentiating his platform as a bishop,” said Blanca Isabel Martínez Bustos, the current director.

Soldiers sexually assaulted a group of women in the municipality of Castaños. The center represented those women, demanding justice and punishment for the perpetrators, as it did for the community of General Cepeda, which opposed the installation of a Center for Integration and Management of Industrial Waste (CIMARI).

The center also allied with the National Observatory Against Femicide, making “Fray Juan visible as a platform for denunciation.” In 2008, the kidnapping of migrants was reported by Pedro Pantoja Arreola, director of Belén, Posada del Migrante, and María Guadalupe Arguello Reyes, “Sister Lupita.”

“It is in the migrant population where this new stage of violence perpetrated by organized crime groups is first expressed,” Blanca pointed out.

Initially led by Sister Silvia Canto, Fray Juan de Larios soon faced escalating violence in the state.

People were reported as having “disappeared” at the Human Rights Center in Saltillo. José Raúl Vera López, Bishop of the Diocese of Saltillo. Photo by Esmeralda Sanchez.

“Pandora’s Box” Opens

“The issue of disappearances exploded,” Fray Raúl said. “I brought Blanca Martínez, and we got the case of a priest whose brother, working in Toluca in an industrial paint factory, disappeared with ten others in two vans. The case was reported to Coahuila authorities.”

“Pandora’s Box was opened through this case,” recalls Bishop Emeritus Vera. People with missing loved ones began to seek advice, highlighting the growing issue of forced disappearances in Mexico. The Human Rights Center of the Diocese formed the first group of relatives of missing persons.

Blanca Martínez Bustos, who received the Sergio Méndez Arceo National Human Rights Award this year, became director on July 31, 2009. Since then, incidents of disappearances, extortions, and confrontations in various places, along with organized crime’s control over municipalities, have been documented.

Women fighting for the presentation of their missing relatives in the Plaza de Armas in Saltillo, next to the Tree of Hope. Photo by Esmeralda Sanchez.

The Coahuila Model

The “Coahuila Model,” developed by then-Governor Humberto Moreira, involved military alliances supposedly to control violence. However, upon her arrival, Martínez faced an attack on the Monclova Municipal Police director, where the aggressors killed his bodyguards.

Cases were documented, and in December 2009, the first group of families of the disappeared was convened. “There were 21 missing people. We worked from the concept of disappearance, understanding the State’s responsibility,” Martínez said.

They decided to denounce it as a group. After a press conference on Dec. 19, 2009, more families joined. In May 2010, with the first march in Mexico City, they adopted the United Forces for Our Disappeared in Coahuila (FUUNDEC), later forming FUNDEM.

As the phenomenon’s scope grew, groups began to take independent paths. Due to violence and financial crises, the lawyers left Martínez alone for some time. Later, Alma García joined from Casa del Migrante.

Juan Enrique Martínez Requenes, head of the Litigation and International Strategy Area since 2018, believes the center’s influence is crucial in Coahuila’s human rights and disappearances agenda.

Strategy and Alliances

In December 2009, federal deputy Rubén Moreira facilitated the first meeting between the prosecutor Jesús Torres Charles and government secretary Armando Luna. The center advised families to maintain high-level dialogues to avoid being ignored.

Establishing an organizational strategy allowed the center to advocate for federal and state laws. In 2010, after discussions with colleagues from Chihuahua and Nuevo León, they positioned the concept of disappearance nationally.

Blanca Martínez, director of the Fray Juan de Larios Center. Photo: Courtesy.

The Regional Human Identification Center followed in Coahuila. Workshops with international experts like Roberto Garretón and Carlos Beristain were pivotal. “It was the gestation of the movement for our missing people,” Martínez recalls.

Families arrived with fear, having faced revictimization, Chamberlain says. An example is the case of Antonio Verástegui González and his son Antonio de Jesús Verástegui Escobedo, who disappeared on Jan. 24, 2009, in Parras de la Fuente, Coahuila.

Yolanda Verástegui González and her brother Juan Manuel searched in vain, even facing lost investigation files. The center provided crucial guidance, helping families engage with authorities and demand justice.

Advocacy and International Strategy

The creation of the Autonomous Working Group in 2013 was a turning point. Acting as a mediator, the group facilitated direct dialogues between the governor, his cabinet, and the families. Chamberlin noted that this change empowered the families to reclaim their agenda.

There was a work school based on Bishop Samuel Ruiz’s teachings, emphasizing victim empowerment.

“It is one of the things that Fray Juan caused and generated a precedent for the rest of the country,” Chamberlain says. “[It] has to do with accompanying the victims, putting them in the center, providing them with the tools that they do not have, to help them organize themselves as subjects.”

In 2015, the center began international advocacy. They positioned the situation before specialized organizations, promoting regional forums to reflect on the General Law of Disappearances. Collaborations with the University of Texas and the International Federation of Human Rights led to reports and communications to the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity.

The body of the fighter María Cristina Vargas is taken back to the Plaza de Armas in Saltillo on May 29. Photo: Esmeralda Sanchez.

The 2017 document “Mexico: Murders, Disappearances, and Torture in Coahuila de Zaragoza Constitute Crimes Against Humanity” highlighted the state’s significant displacement due to violence. The report detailed cases where police colluded with Los Zetas, a group of former military special forces working as a drug cartel, for territorial control.

The 2011 “Mission Report, Forced Disappearance in Mexico” was the first international report to show the magnitude of the problem clearly.

For Chamberlin, this report marked Fray Juan’s impact on the country since it contained recommendations that led to government actions, including the crime of forced disappearance in the Penal Codes of all federal entities and the approval of a general law on forced or involuntary disappearances.

“It was the first international report that made the dimension of the problem of disappearances more clearly visible.

The Current Stage and Future of Fray Juan

Today, Fray Juan has documented nearly 750 cases of missing persons. The center advises families to collectively defend common rights and not rely solely on legal representation.

The center’s future goals include a diversified presence in addressing citizens’ needs across regions and pushing for systemic changes, such as taking cases to court and proposing laws.

Judge Luis Efrén Ríos emphasized that all actors are crucial for the model to work. “The center is the families, but alongside them are their defenders, a role key that a center like Fray Juan De Larios has.”

Despite the work done, the primary pending task is locating the missing and ensuring justice. Families like the Verásteguis continue to await answers and justice.

For Fray Raúl Vera, the government’s response has been inadequate. “Forced disappearances continue to grow. The problem stems from government corruption, and crime remains rampant despite leniency policies.”

Fray Juan De Larios remains essential, with its work more relevant than ever in the current context.